The Data Science Lifecycle

motivating our selected data science lifecycle and how different lifecycles make value judgements about what exactly data represents in our world.

Introduction

To take an interdisciplinary perspective on aligning what we should do and our moral duties to stakeholders with our actual data science practices, we must understand where common ethics topics emerge in data science. This requires us to choose a data science lifecycle that characterizes how interactions with our world are transformed into data models. Though it might not be explicit, choosing one lifecycle over another endorses specific views about data, data models, and their respective relationships to what we interpret as knowledge about our world. Thus, the choice to use a certain data science lifecycle is value-laden, an important point to reiterate to students. Below, we describe the relational view of data and data models, a framework that is likely very familiar to statisticians and data scientists.

Examples of Data Models:

A simple linear regression that uses years of education to model a person’s expected income.

An algorithm that utilizes millions of hyperparameters to predict an incarcerated individual’s risk of recidivism.

A data visualization that describes a relationship between variables within a sample.

The Relational View of Data and Data Models

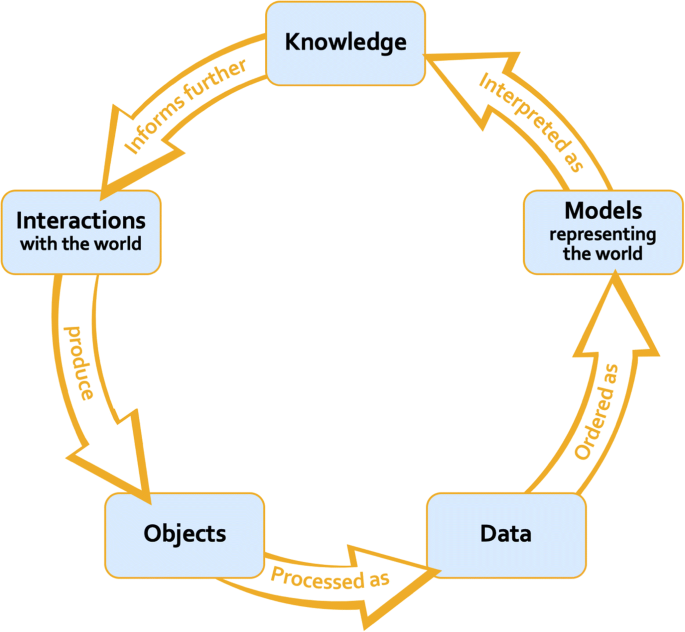

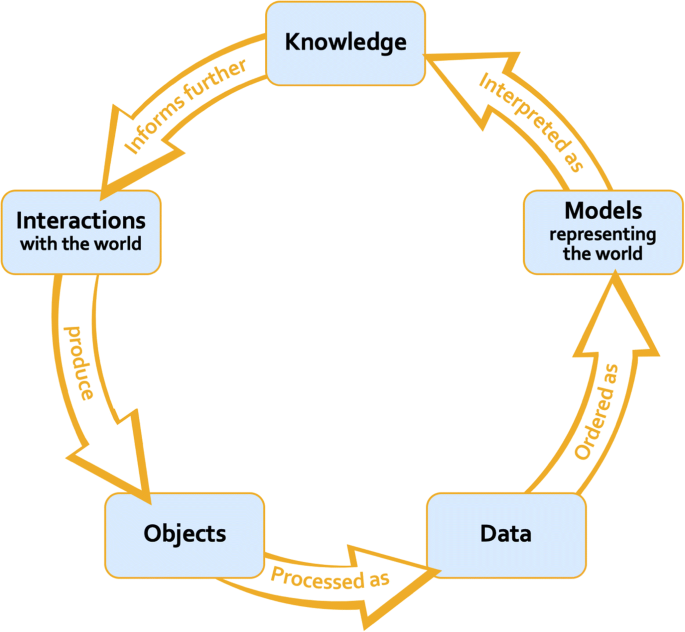

Under the relational view of data and data models, data is understood as an object that is treated as evidence for a claim about the world and that can be circulated amongst individuals or groups (Leonelli, 2019). The informational content of data depends on the researchers’ background assumptions and social context. So, information is not inherent to the data but is instead defined by the social environment in which the data is collected and the function the data is supposed to serve. The view that context plays an integral role in what data represents is also emphasized within the statistics community. As statisticians George Cobb and Thomas Moore famously claimed, ``[data] are numbers with a context” (Cobb & Moore, 1997). Given data is context-sensitive in the sense that its informational content is influenced by researchers’ assumptions and social contexts, data models (rather than the data itself) are taken to represent relationships in our world under the relational view. Thus, the relational view of data and data models highlights that data models are a necessary and highly influential aspect of what we take to be knowledge about our world in data science (Leonelli, 2019).

The Final Data Science Lifecycle

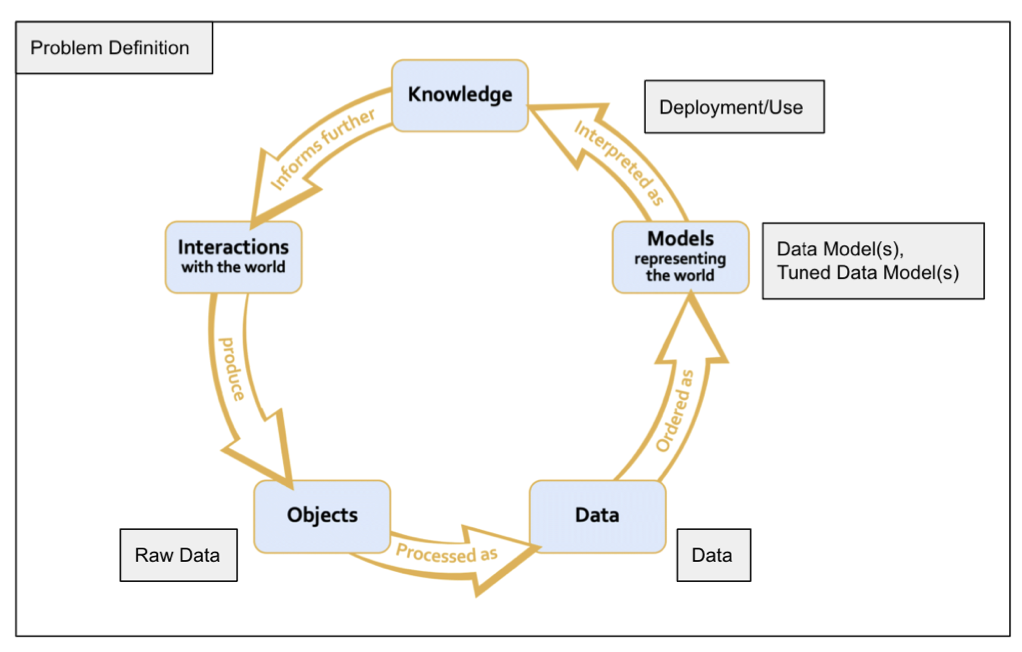

Given that the relational view aligns well with data science examples (see Appendix), we use the data science lifecycle in Figure 2 throughout this paper and on the associated website. Beyond aligning well with data science examples, the lifecycle shown in Figure 2 also fits with the data science processes described in what is data science ethics?. Figure 2 showcases how the data science processes connect to our final data science lifecycle. However, other data science lifecycles could also be compatible with the relational view of data and data models as well as the described data science processes (we outline some potential shortcomings of our final lifecycle in the Appendix for instructors who want to have their students walk through the pros and cons of working with different versions of the data science lifecycle). As such, we acknowledge that our selected lifestyle, depicted in Figure 2, is not the only viable choice.

Appendix

In the appendix, we provide worked-out examples and describe some of the limitations of the lifecycle we used in this paper to underscore the value of judgment in defining relationships between data, the world, and knowledge. We hope that our examples lead to interesting and fruitful classroom discussions.

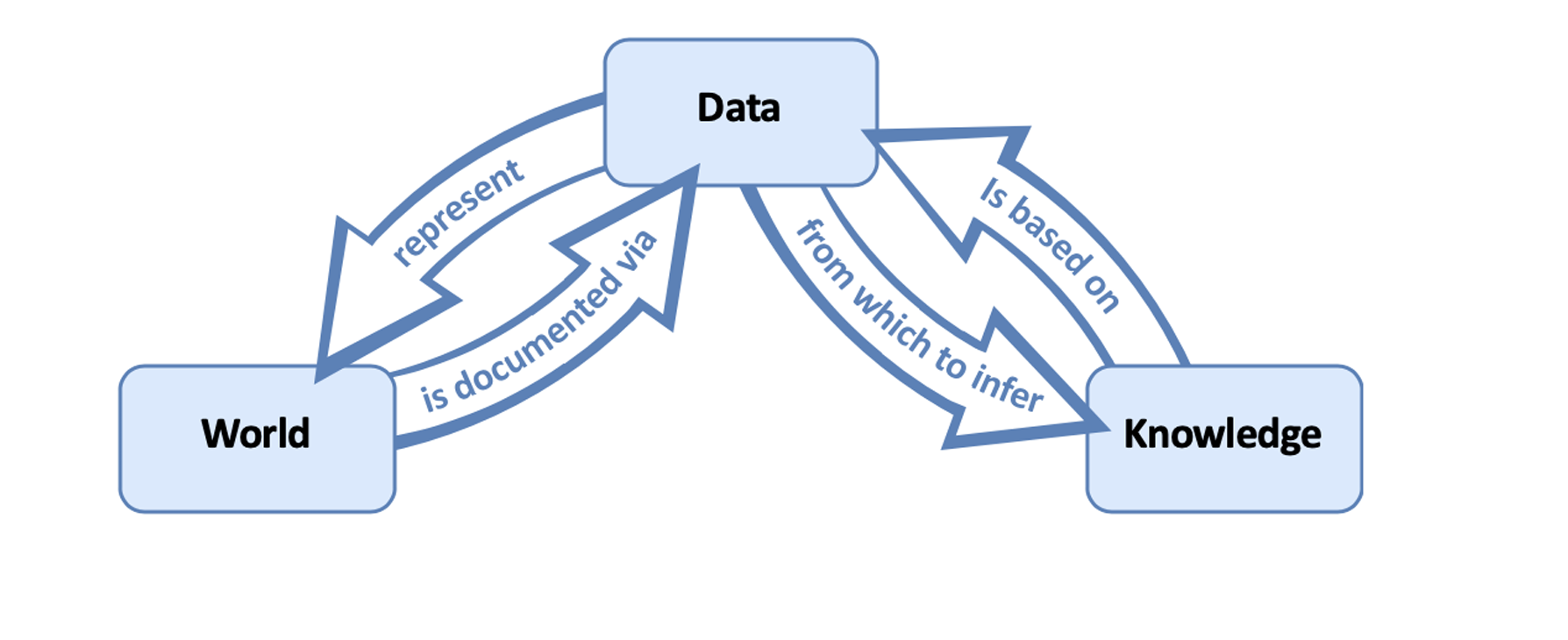

Even though, as highlighted in the relational view of data and data models subsection, it makes the most sense to think of data and data models using a relational view, it is worth noting (and pointing out to students) that there exist alternative frameworks in which to consider data and data models. Here, we examine the representational view of data, data models, and their connections to what we interpret as knowledge about our world (Leonelli, 2019).

The Representational View

Under the representational view of data and data models (see Figure 3), the informational content of data is fixed and independent of the researchers’ background assumptions and context. Thus, data models are only important insofar as they extract the underlying truth from the data. So, under the representational view, data models are either correct or incorrect, depending on their ability to elucidate the truth stored in the data. In other words, data are simply numbers that hold information, and data models (and other methods of processing data) are only relevant because they clarify the connections between data and what we interpret to be knowledge (Leonelli, 2019).1

The Relational vs. Representational View In-Practice

Final Data Science Lifecycle Caveats

For instructors who seek to walk their students through the advantages and disadvantages of specific data science lifecycles, we note some flaws with our selected lifecycle (see Figure 2). First, the arrows between the data science stages imply that the data science is linear (i.e., only when all prior steps are complete is the next step pursued). However, in practice, data science is iterative; for example, data scientists may build a data model, realize their model underperforms on a certain group, and then collect more data to improve the model’s performance. Another shortcoming of our final lifecycle in Figure Figure 2 is that it does not highlight how many different people (or groups) are often involved in different stages of the lifecycle. For instance, a company might collect the data and then bring in an external group of data scientists to create a meaningful model from that data. The fact that different people (or groups) act at different stages of data science is essential both for understanding how data science practices are actually carried out as well as why understanding certain ethics topics (such as moral responsibility) is integral to data science. As such, we move forward with our final data science lifecycle in the spirit of George E. P. Box, “all models are wrong, but some are useful,” (Box, 1979).

References

Footnotes

What we interpret as knowledge is not the same as actual knowledge. E.g., the statement “the Earth is flat” was historically interpreted as knowledge, even though it is a false statement and thus not actual knowledge.↩︎